In 2022, municipal properties in Philadelphia used over 700,000 megawatt hours (MWh) of electricity. This amount of electricity adds 333,798 tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, which is equivalent to one gas-powered car driving over 770 million miles1. The city is currently striving to reduce its emissions through increased use of renewable energy and innovation in the transportation sector. Philadelphia’s Municipal Master Plan aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50%, cut energy use by 20%, and generate 100% of all electricity for city facilities from renewable resources, all by 20302. As of February 2024, renewable energy accounts for about 8% of the city’s electricity demand. Therefore, this is a lofty goal, but the city is showing steady improvement in its clean energy transition.

Renewable Energy

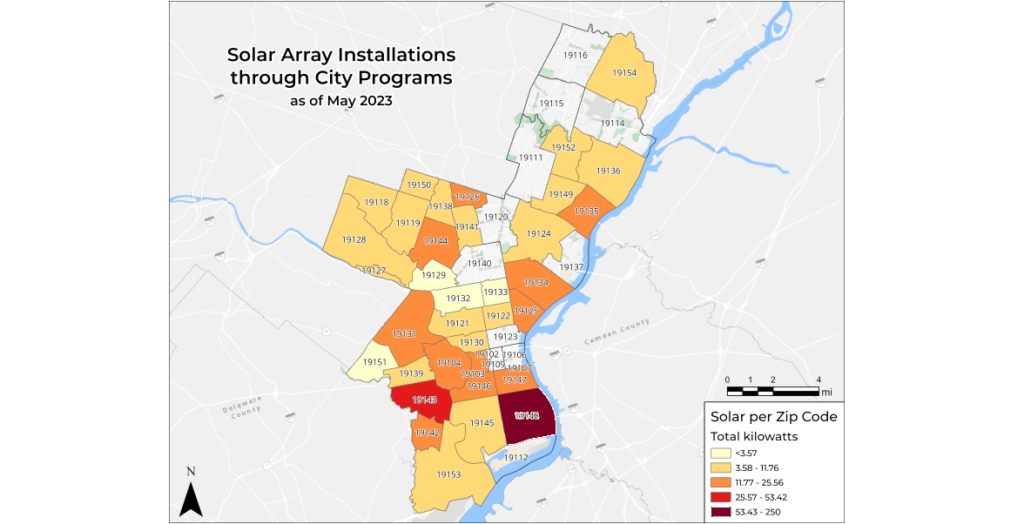

One of Philadelphia’s most significant strides in renewable energy is its commitment to transitioning to solar power. The city of Philadelphia purchases renewable energy certificates (RECs) through the Philadelphia Energy Authority (PEA) programs Solarize Philly, Share the Sun, and Solar Savings Grants. The development of a massive solar project in Adams County is also underway, which will further increase Philadelphia’s use of solar power. This 230,000 solar panel field covers about 700 acres near Gettysburg, and will supply enough renewable energy to power approximately 23% to 25% of the city’s electricity. The solar farm is owned and operated by Energix, a company with offices in the U.S., Poland, and Israel. The energy itself does not go directly to Philadelphia’s buildings through transmission lines, but rather flows into the power grid. While solar energy may not always directly reach municipal buildings, the RECs increase the city’s renewable energy portfolio while providing solar panels for low and moderate income residents. In fact, all proceeds from the City’s RECs purchase will be reinvested into more solar projects for low- and moderate-income households, creating a sustained cycle of funding for affordable solar installations around Philadelphia3. Additionally, it has been revealed that across the Mid-Atlantic region including Philadelphia, prior to the pandemic, more than 30% of all renters and 50% of Black households reported facing energy insecurity during the year, unable to afford necessities like food due to the obligation to pay for energy bills. For vulnerable households, especially those who are disproportionately impacted by climate change, affordable rooftop solar can help relieve energy insecurity and increase the value of their homes3. This upholds the social justice and equitability aspects of sustainability. In tandem with its solar power initiatives, the city has also launched the Streetlight Improvement Plan, in which 100,000 street lamps will be replaced with energy-efficient LED bulbs. This change is expected to halve the city’s street light electricity usage2.

There are, however, some limitations to transitioning to renewable energy in Philadelphia. One of the primary challenges is integrating renewable energy infrastructure into the existing urban landscape. The city’s historic buildings and densely packed neighborhoods limit potential for extensive solar installations, which means that solar farms take up significant space in areas farther from the city. It also poses a challenge ensuring equitable access to renewable energy resources across all communities, regardless of their economic status2. Cost is a major criticism of solar power, as PV panels have been too expensive for significant market penetration. However, they are rapidly becoming more affordable. The creation and disposal of solar panels is another concern, as they are created from extracted earth materials that are rare and expensive, and their extraction involves some ethical implications. Newer solar panel technologies are moving toward utilizing more common metals. Moreover, fabricating solar panels also involves caustic chemicals that have resulted in toxic spills. While this needs to be controlled, the amount of chemical output is still significantly less than that of the fossil fuel industry. Another concern is the disposal of solar panels that are no longer functional, as there are currently limited recycling opportunities. This is why sustainability standards are currently being created for solar panel construction, with the materials’ recyclability in mind. Many opportunities for solar power in Philadelphia are yet to be taken advantage of. The city could begin to encourage rooftop solar panels on residential and commercial buildings, and drive innovation through partnerships with academic institutions, making solar energy both more accessible and more sustainable.

With all this in mind, the implementation of solar energy involves numerous stakeholders. This extends from the residents of Philadelphia, to corporations, to beyond the city. Constructing a massive solar field would likely involve some significant tree removal, and would affect those that live near that plot of land. The materials involved in the manufacturing of solar panels are extracted from overseas, bringing foreign stakeholders into play. There are many moving parts in the implementation of clean energy, which is part of what makes this infrastructural change a massive undertaking on a large scale.

Transportation

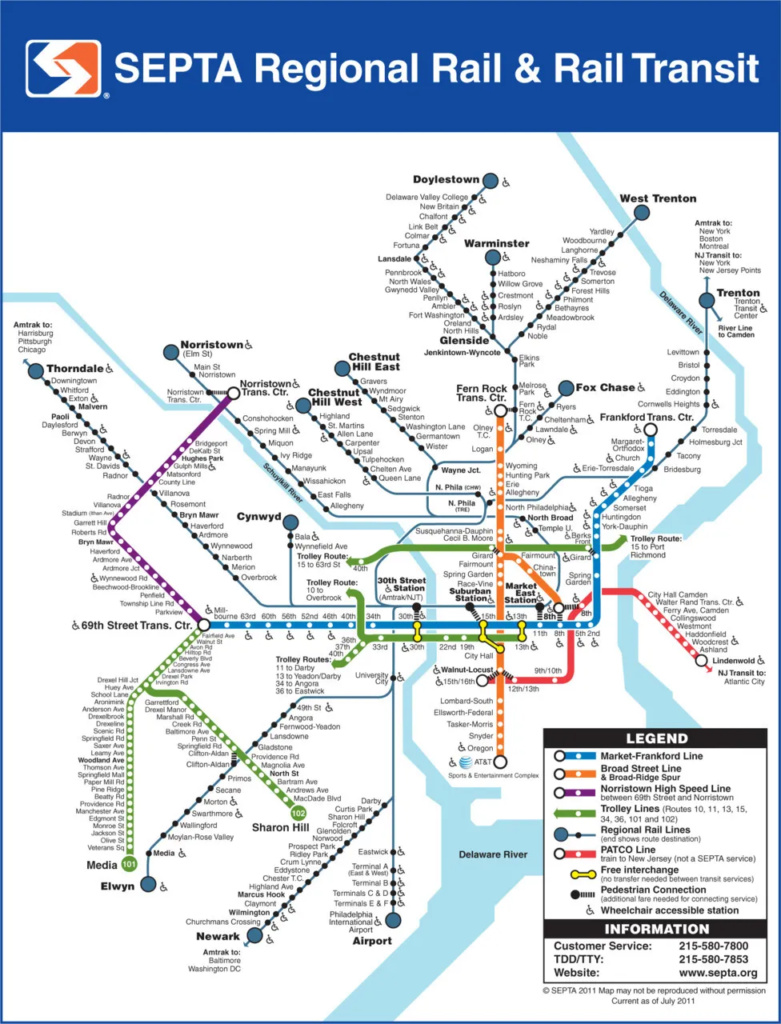

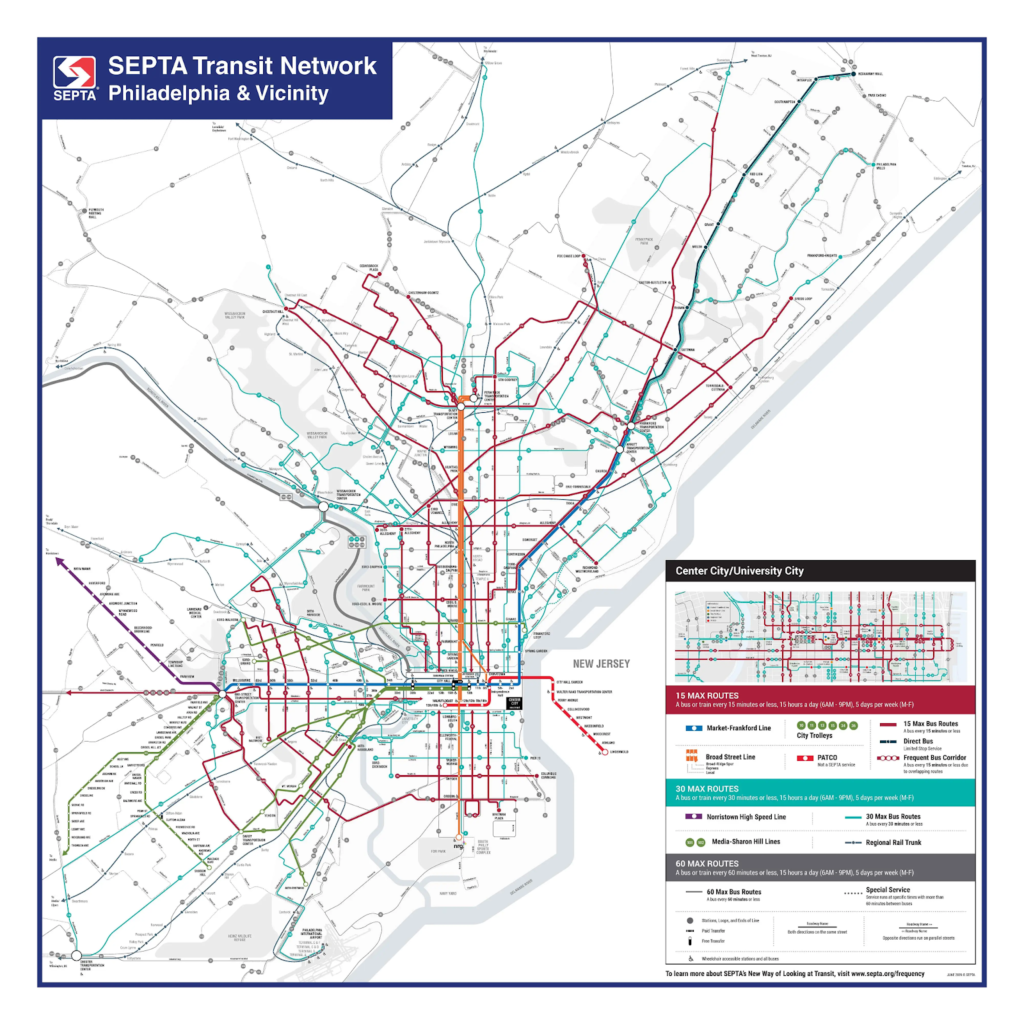

Philadelphia also aims to reduce emissions through increased use of public transportation, integration of pedestrian friendly infrastructure, and an increased use of electric vehicles. The Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability oversees several interconnected city departments and divisions, such as the city’s Complete Streets program, the Department of Streets, the Office of Sustainability, and the Philadelphia Water Department. The Complete Streets Policy focuses on pedestrian friendly infrastructure, so that city residents can safely walk or bike on city streets. Clean Air Action’s Feet First Philly initiative also focuses on advocacy for a more sustainable transportation system, which includes supporting greater public transit use, bicycling, and walking. Their initiatives include a council-sponsored pedestrian-oriented program at Drexel University, a bi-monthly newsletter, collaborating with the local government to improve conditions for pedestrians, and surveying intersections to evaluate pedestrian safety and accessibility. Philadelphia is already rated one of the best walking cities in the country, with a walkability score of 88/100, however, walking is not always the most efficient for those with longer commutes. Philadelphia also has recently been putting more emphasis on its public transit system, SEPTA. SEPTA provides a regional rail system that reaches into the outskirts of the city, as well as a bus system. The regional rail provides a convenient, affordable option for those who commute into the city from surrounding suburbs. In order to further promote sustainable transportation options, SEPTA is partnering with Mural Arts Philadelphiafor the collaborative project Getting to Green: Routes to Roots. Through mural art, the project aims to promote the use of public transit for exploring Philadelphia’s parks and natural landscapes4. The vehicles themselves are also part of one of the cleanest bus fleets in the nation, as over 90% of SEPTA’s current buses are electric-diesel hybrids. However, SEPTA is about to get even greener, as Philadelphia increases its usage of electric vehicles5.

As of February 2023, SEPTA approved a contract for the purchase of 10 fuel cell electric buses (FCEBs). FCEBs are powered by electricity derived from hydrogen fuel cells, resulting in zero tailpipe emissions. This will overall improve air quality for riders, neighbors, and communities. Hydrogen buses are comparable to diesel-hybrid buses in terms of range and performance, but they are much quieter, which would cut down on city noise pollution. They also have lower maintenance costs, and less than half the lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions. These new vehicles are expected to be implemented in the summer of 2024. Additionally, in 2023, the city of Philadelphia reached a fleet of 250 electric municipal vehicles, which include garbage trucks, police cruisers, and Water Department vehicles. However, this is out of a fleet of 5,000 vehicles, so the city still has a significant way to go. The city’s strategy is to replace its vehicles with cleaner versions as the old ones retire, instead of all at once. This is sustainable in and of itself, given that disposing of thousands of functional vehicles isn’t an environmentally conscious move, even if the goal is to replace said vehicles with greener alternatives.

Slowly but surely, Philadelphia plans to stop buying new fossil fuel-powered vehicles by 20306. There are some limitations to this, as larger vehicles are a lot more difficult and expensive to electrify. Moreover, despite increased commercial use of electric vehicles, the city Philadelphia lacks adequate access to charging stations7. In order to fully electrify Philadelphia’s vehicles, larger infrastructural change will need to take place. Gradually, electric vehicles have grown more popular commercially, but in an urban environment like Philadelphia, only electric municipal vehicles prove necessary. Some stakeholders involved in these transportation improvements are public transportation systems, such as SEPTA, as well as car manufacturers and the residents of Philadelphia. There also may be international stakeholders involved, as the materials sourced to make electric vehicles are often extracted overseas. Cobalt, Lithium, and Nickel are all necessary in order to manufacture a rechargeable lithium ion battery. Half of the world’s cobalt originates from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Indonesia, Australia, and Brazil make up the lion’s share of global nickel reserves. South America’s ‘Lithium Triangle’ – consisting of Bolivia, Chile and Argentina – holds 75% of the world’s lithium7. The extraction of these precious metals involves difficult manual labor in unsafe conditions, which presents ethical implications when considering the social justice implications of electric vehicles. For the public, the most significant focuses should be on walkability and public transportation. Those types of infrastructural improvements limit the need for vehicle building materials, and are also much more affordable, catering to all socio-economic needs instead of just to those that can afford electric vehicles.

List of assets for energy & transportation:

- Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability

- Solar Panel Companies:

- Arsenal Solar

- Imperium Solar

- Solar Techs

- PA Green Solar

- Whitaker Renewables

- Second Sun Solar

- Helio Power Systems

- SEPTA rail & bus station maps

References

2Clean Choice Energy. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://cleanchoiceenergy.com/news/renewable-energy-in-philadelphia.

3Chi, Dora. 2022. “Local programs make solar affordable and bring City closer to renewable energy goal | Office of Sustainability.” Phila.gov. https://www.phila.gov/2022-06-01-local-programs-make-solar-affordable-and-bring-city-closer-to-renewable-energy-goal/.

“Clean Air Council » Feet First Philly – Philadelphia.” Clean Air Council. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://cleanair.org/sustainable-transportation/feet-first-philly/.

7Egan, Teague. 2023. “Where do electric vehicle batteries come from?” EnergyX. https://energyx.com/blog/where-do-electric-vehicle-ev-batteries-come-from/.

4“Getting to Green: Routes to Roots.” 2023. SEPTA. https://iseptaphilly.com/blog/gettingtogreen.

“Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability | Homepage.” n.d. Phila.gov. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://www.phila.gov/departments/office-of-transportation-infrastructure-sustainability/.

6Schmidt, Sophia. 2024. “Philly buys more electric vehicles for municipal fleet.” WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/philadelphia-city-electric-vehicle-fleet/.

5“SEPTA Board Approves Purchase of 10 Fuel Cell Buses | SEPTA.” 2023. Septa. https://wwww.septa.org/news/septa-board-approves-purchase-of-10-fuel-cell-buses/.

1Shade, Charlotte. 2023. “Mapping Solar Power in Philadelphia | Office of Sustainability.” Phila.gov. https://www.phila.gov/2023-07-31-mapping-solar-power-in-philadelphia/.

“Solarize Philly.” n.d. Philadelphia Energy Authority. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://philaenergy.org/programs-initiatives/solarize-philly/.

7Vargas, Claudia. 2023. “Hundreds of EVs in Philly, not enough chargers.” NBC10 Philadelphia. https://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/investigations/philly-buys-hundreds-of-electric-vehicles-but-not-enough-chargers/3730971/.