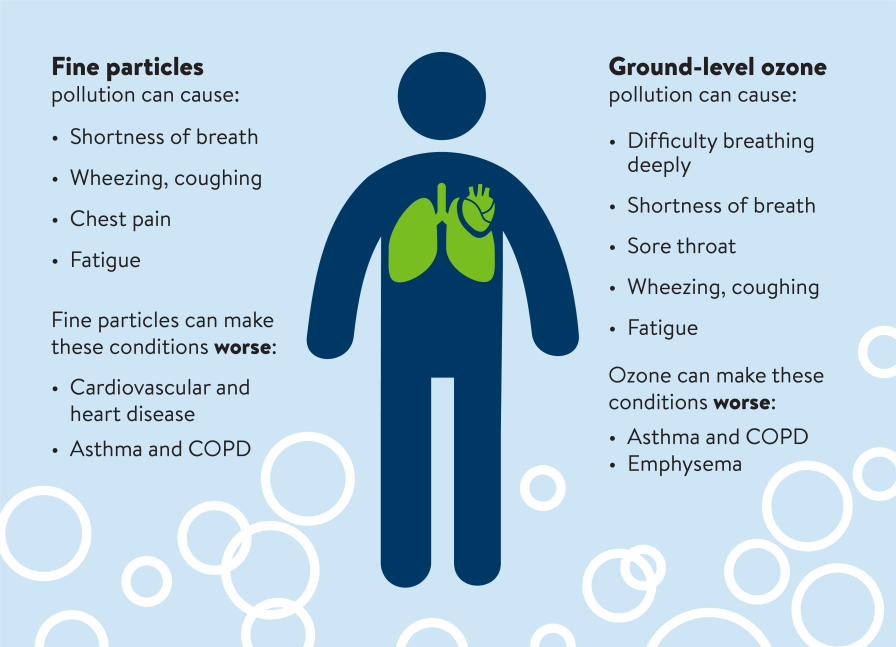

Air pollution is a significant concern in urban areas such as Philadelphia. According to the EPA1, the 6 criteria air pollutants are ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, lead, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide. The presence of these pollutants can be hazardous to human health, as poor air quality has shown strong linkages to increased cases of stroke, heart disease, pulmonary disease, lung cancer, pneumonia, and asthma2. Air pollution also exacerbates climate change, as several pollutants are also greenhouse gasses. The primary greenhouse gasses are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone. Not all greenhouse gasses are considered criteria pollutants since they occur naturally in the atmosphere, but in excessive amounts they lead to the retention of heat within the upper atmosphere. Any pollutants that are not naturally occurring in the atmosphere are considered anthropogenic pollutants. Anthropogenic pollutants are classified as either primary or secondary pollutants. Primary pollutants are released into the air directly from an exact source, whereas secondary pollutants are a result of chemical reactions that happen from compounds mixing within the atmosphere. In a city environment like that of Philadelphia, there are both primary and secondary pollutants present. The primary sources of pollutants in this type of environment are factories, industry, vehicles, and air traffic.

The city of Philadelphia has high levels of particulate matter and ozone in its atmosphere. In 2020 a report from The American Lung Association found that the greater Philadelphia metro area ranked as the 12th most polluted city in the United States for its year-round average levels of fine particle pollution and as the 23rd most polluted for days with high levels of ozone smog3. Ozone is a secondary pollutant formed through chemical reactions between volatile organic compounds (VOCs), oxides of nitrogen, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight. These chemical reactions happen when anthropogenic pollutants such as nitrogen oxides are emitted from vehicles, factories and other industrial sources, fossil fuels, combustion, consumer products, evaporation of paints, and then react with other compounds in the atmosphere4. Breathing in this pollutant can worsen chronic lung conditions such as asthma. Particulate matter can be emitted from cars, trucks, factories, coal fired power plants, and wood burning devices3. The city of Philadelphia is highly industrialized, with factories, warehouses, industrial plants, and smoke stacks lining I-95, a massive highway that runs directly into the city. Like other U.S. cities, there is also significant vehicle use, despite its high walkability score. Vehicles burning gasoline and diesel fuel emit greenhouse gasses, along with harmful air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, benzene, and formaldehyde5.

Although Philadelphia still ranks as significantly polluted with ozone and particulate matter in comparison to other U.S. cities, the American Lung Association’s report has also found that Philadelphia’s daily measurements of these pollutants have improved to their best yet. Moreover, the AQI (air quality index) in Philadelphia remains “good” for the majority of the time, with only very seldom dips into the “moderate” category6. This improved air quality could likely be associated with the successes of the Clean Air Act, along with other regulations, councils, and infrastructure changes implemented within the city. Efforts made to alleviate air pollution are led by a range of stakeholders, including residents of the city who worry for their own health, as well as several organizations and agencies that aim to monitor and improve air quality. A significant stakeholder organization in the Philadelphia region is the Clean Air Council, a member-supported environmental organization dedicated to protecting and defending everyone’s right to a healthy environment7. Within our greater working definition of sustainability, their mission honors social justice initiatives and uplifts the idea that a healthy environment is a basic human right. The Clean Air Council uses public education, community action, government oversight, and enforcement of environmental laws to work through a broad array of related sustainability and public health initiatives in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. The Clean Air Council has deployed air monitors in Northeast Philadelphia, has created a website to track truck illegal idling in the Philadelphia area, and has provided pedestrian advocacy through its “Feet First Philly” initiative in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by promoting walking and bicycling as an alternative to vehicle usage. These are just a few examples of the Council’s initiatives as stakeholders. The city of Philadelphia’s Air Pollution Control Board is also a crucial asset to monitoring and mitigating air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. As one of the city council’s several environmentally focused departments, the Air Pollution Control Board advises the Department of Public Health on air quality issues and promotes regulations that protect air quality standards, control air contaminants, and establish air quality objectives8. This means that the Department of Public Health is also a relevant stakeholder, as its mission is to protect and promote the health of all Philadelphians, providing assistance to those that may be disproportionately impacted by health complications or limited access to healthcare9, once again honoring sustainability’s inherent link to social justice and wellbeing. The overarching Office of Sustainability within Philadelphia’s city council can also be deemed a relevant stakeholder, as it works toward environmental justice and aims to reduce carbon emissions through advocacy, education, policymaking, and instituting benchmarks for energy use and clean energy transition10.

A number of initiatives are in place in Philadelphia as an effort to combat air pollution and climate change. City greening initiatives, such as converting brownfields to parks and implementing rooftop gardens, clean the air by regulating carbon in the atmosphere. The city’s walkability also plays a role in reducing carbon emissions, along with infrastructure assets such as the SEPTA public transportation system. The city of Philadelphia encourages residents to consider walking, biking, or taking SEPTA to their desired destination, limiting idling in their vehicles, and to consider vehicle emissions when purchasing a new car11. Possible limitations to these proposed solutions are efficiency and reliability. Many residents may prefer their car over walking if they need to get to another part of the city quickly, and public transportation may not be perfectly reliable or convenient with their schedules. Public transportation is heavily utilized in Philadelphia, and the city boasts a high level of walkability, yet it is still largely vehicle reliant. Increased usage of electric vehicles may help to mitigate emissions. On the whole, the city of Philadelphia aims to switch to renewable energy resources such as solar energy in an effort to generate or purchase renewable energy for 100% of its electricity by 2030, and achieve carbon neutrality by 205012. Switching to solar energy would decrease greenhouse gas emissions, as electric power generation is the second largest emitter of carbon dioxide pollution13. However, there are some limitations to the widespread implementation of solar power, such as the fact that it may be inconsistent due to its weather dependency, its expense, and the fact that solar panels take up significant space and are difficult to dispose of. Still, when considering cost-benefit analysis, the anticipated benefits of switching to renewable resources outweigh these potential limitations.

From a policy standpoint, Philadelphia has recently approved a revision by the city’s Health Department for regulation of carcinogenic compounds such as asbestos, lead, arsenic, and benzene emitted from facilities in the city14. Just recently, in February 2024, the EPA has implemented a new soot standard for the Philadelphia region, aiming to reduce fine particulate matter pollution. Fine particulate matter can enter the lungs and bloodstream, increasing incidences of asthma attacks, heart attacks, and cancer. This new, stricter standard lowers the concentration of allowable PM2.5 pollution in the air by 25% — a change EPA predicts could prevent thousands of premature deaths in 203215. This policy also aims to address the social justice implications of disproportionate exposure to particulate pollution among racial and socioeconomic groups, as it has been found that Black and Hispanic children are hospitalized for asthma symptoms at much higher rates than White and Asian children in Philadelphia15. Asthma hospitalizations are much higher in certain neighborhoods of the city, such as lower Northeast, upper North, and West Philadelphia. This new EPA implemented standard honors environmental health as a human right, and will hopefully prove successful in cutting down industrial emissions of fine particulate matter. Philadelphia’s air is cleaner than it has been in decades, as stakeholders work toward infrastructural changes and policy initiatives that honor human wellbeing as an entity of sustainability. However, continued individual, industrial, and governmental efforts to mitigate emissions are crucial to maintenance and improvement of the city’s air quality and residential health and wellbeing.

List of assets for air pollution & climate change:

- Clean Air Council, 135 S 19th St Suite 300, Philadelphia, PA 19103

- Philadelphia Air Management Lab, 1501 E Lycoming St, Philadelphia, PA 19124

- Air Management Services, 321 S University Ave, Philadelphia, PA 19104

- Office of Sustainability, 1515 Arch St, Philadelphia, PA 19102

References

2“Air quality, energy and health.” n.d. World Health Organization (WHO). Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/air-quality-energy-and-health/health-impacts.

12Chi, Dora. 2022. “Local programs make solar affordable and bring City closer to renewable energy goal | Office of Sustainability.” City of Philadelphia. https://www.phila.gov/2022-06-01-local-programs-make-solar-affordable-and-bring-city-closer-to-renewable-energy-goal/.

7“Clean Air Council » Mission and Vision.” n.d. Clean Air Council. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://cleanair.org/mission-and-vision/.

1“Criteria Air Pollutants | US EPA.” n.d. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/criteria-air-pollutants.

9“Department of Public Health | Homepage.” n.d. City of Philadelphia. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.phila.gov/departments/department-of-public-health/.

11Harvey, LeAnne. 2017. “8 simple ways to make Philly greener | Office of Sustainability | Posts.” City of Philadelphia. https://www.phila.gov/posts/office-of-sustainability/2017-02-16-8-simple-ways-to-make-philly-greener/.

13“Human Health & Environmental Impacts of the Electric Power Sector | US EPA.” 2023. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). https://www.epa.gov/power-sector/human-health-environmental-impacts-electric-power-sector.

8Lee, Emma. n.d. “Air Pollution Control Board | Homepage.” City of Philadelphia. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.phila.gov/departments/air-pollution-control-board/.

10“Office of Sustainability | Homepage.” n.d. City of Philadelphia. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.phila.gov/departments/office-of-sustainability/.

6“Philadelphia Air Quality Index (AQI) and Pennsylvania Air Pollution.” 2024. IQAir. https://www.iqair.com/us/usa/pennsylvania/philadelphia.

3“Press Releases | American Lung Association.” n.d. Press Releases | American Lung Association | American Lung Association. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.lung.org/media/press-releases/state-of-the-air-philadelphia.

5“Reducing car pollution – Washington State Department of Ecology.” n.d. Department of Ecology. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://ecology.wa.gov/issues-and-local-projects/education-training/what-you-can-do/reducing-car-pollution.

14Schmidt, Sophia. 2023. “Philly toxic air pollution: What you need to know.” WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/philadelphia-toxic-pollution-changes-three-things-to-know/.

15Schmidt, Sophia. 2024. “Philly air quality: New federal standard limits fine particles.” WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/new-epa-soot-standard-air-quality-pollution/.

4“What is Ozone? | California Air Resources Board.” 2020. California Air Resources Board. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/fact-sheets/what-ozone.