Drinking Water & Water Resources in Philadelphia

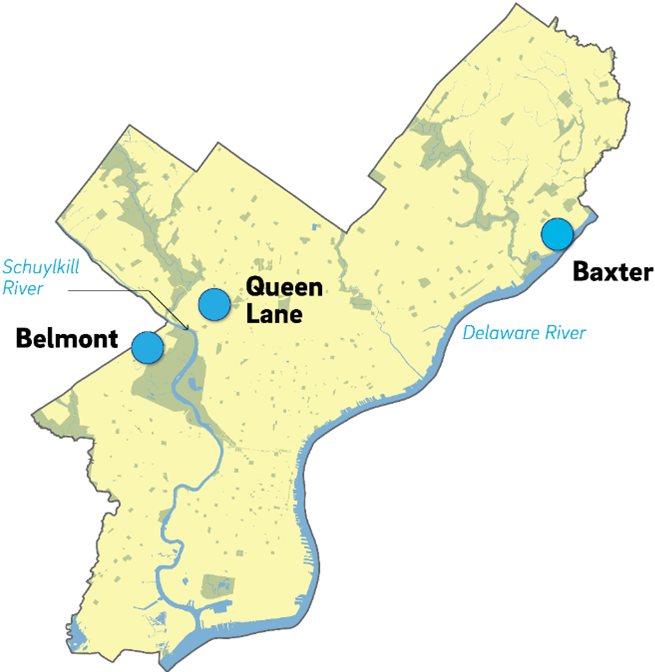

Philadelphia gets all of its drinking water from surface water. 58% of Philadelphia’s water is from the Delaware River with the rest sourced from the Schuylkill river1. Both rivers are considered safe sources for drinking water that meets EPA standards post treatment. Still, there are some contaminants found in tap water that raise health concerns in the Philadelphia region.

Contaminants

The pollutants of most significant concern in the area are lead, chromium 6, and Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Lead contamination is a result of older lead plumbing, rather than the actual drinking water source itself. Recent estimates indicate that Philadelphia has over 20,000 homes with lead service pipes, and therefore 10% of Philadelphia’s water quality samples collected for lead analysis are reported to be 3 parts per billion or higher, but the risk of lead in drinking water is much higher than that number suggests2. The EPA and CDC have determined that there is no safe level of lead to be consumed by children. Therefore, the city of Philadelphia suggests that those in homes built prior to 1987 should install a water filtration system that is certified for lead removal. However, filtration systems may not be so affordable for low income households.

Chromium 6 is another highly toxic metal found in drinking water, and it is not regulated by the EPA. According to testing conducted by the Environmental Working Group, Philadelphia was measured to have Chromium 6 levels that are 11-37.5 times higher than the level generally accepted as safe. Ingesting Chromium 6 through drinking water can increase the risk of stomach cancer and reproductive issues2.

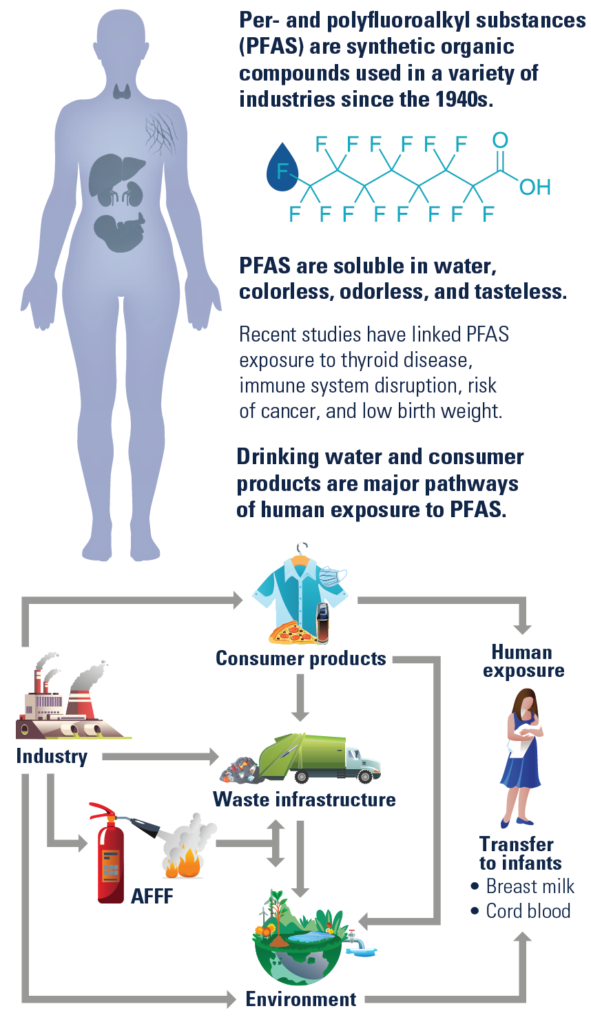

Philadelphia has high rates of PFAS contamination. PFAS are a category of emerging contaminants commonly used in firefighting foam, Teflon, non-stick surfaces, stain-resistant surfaces, and food packaging. There are more than 9,000 variants of PFAS, and they are known as “forever chemicals” because they do not easily degrade in the environment and are very difficult to extract or destroy. The sources of PFAS contamination include industrial and manufacturing facilities, landfills where PFAS have leached into groundwater, and places where PFAS-based firefighting foam has been used such as airports, military sites, chemical plants, and aboveground petroleum storage facilities. High levels of PFAS in drinking water are much more common in highly industrialized urban areas such as Philadelphia3. A study from the U.S. Geological Survey discovered that more than 70% of Pennsylvania rivers and streams contain PFAS, including the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers4. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) has determined that PFAS exposure is associated with various adverse health effects, including an increased risk of cancer, lowered fertility rates, and developmental issues in infants and young children2.

A Personal Note on PFAs Contamination

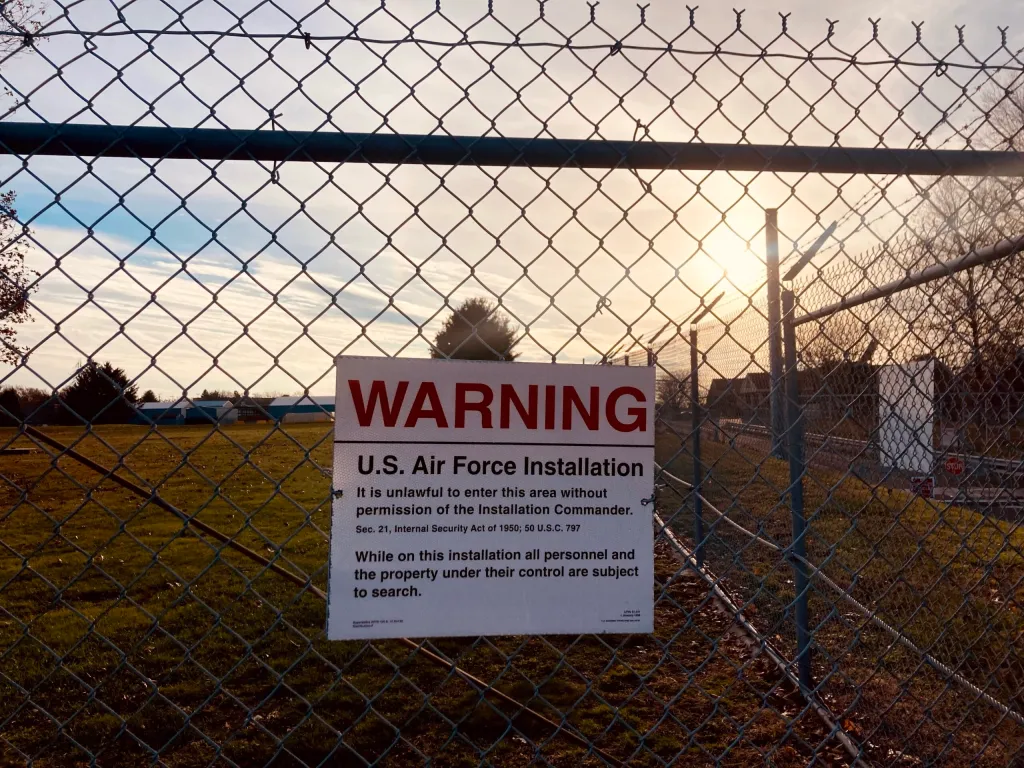

For over twenty years, my family has lived in Huntingdon Valley, PA, just 11 miles to Center City Philadelphia. We have been drinking tap water since moving to the area in 1997, and in 2018, my father was diagnosed with bladder cancer. Fortunately, the cancer was caught at an early stage and was treated successfully, but as a fit, 52-year-old non-smoker who had not shown signs of being genetically predisposed to cancer, this was a confounding revelation. We theorized that his condition could be linked back to our drinking water. We live just downstream from a superfund site – the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Willow Grove – with the Pennypack Creek running through the area. The Pennypack Creek flows through Philadelphia and empties out in the Delaware River, where 58% Philadelphia’s drinking water is supplied from. The nearby naval air base used PFAS containing fire-extinguishing foams that have seeped into the groundwater5. To measure PFAS exposure in residents of the Philadelphia region, our zip code was listed as eligible for subsidized PFAS blood testing. PFAS levels are considered high if a blood sample finds anything over 20 nanograms per milliliter. When my father received his test results, his overall PFAS levels were 46.17 nanograms per milliliter. These results placed him in the top 30% of subjects in the high-risk category. Ever since my father’s diagnosis, my family has avoided tap water and instead has bottled water delivered to our doorstep. An article I wrote for The Allentown Voice elaborates on my family’s experience with PFAS contamination.

Additional Concerns

An additional water related issue in the City of Philadelphia is the overflow of the sewer system when there is excessive rainfall. This is especially a recurring issue in the older parts of the city. This is due to the fact that urban areas are dominated by impervious surfaces such as pavement, concrete, and buildings.

Areas with this kind of coverage cannot adequately absorb stormwater, and as a result, billions of gallons of stormwater and diluted sewage flow into local waterways each year6. Since the waterways surrounding the city are the predominant source of drinking water, this overflow can result in concerns for the river ecosystem and for human health.

Stakeholders & Interest Groups

Several organizations within the city of Philadelphia are committed to ensuring that drinking water resources are viable. The Philadelphia Water Department is one of the most prominent stakeholders regarding the city’s water supply, as it is the department responsible for ensuring that the city’s water supply is clean and safe. The department utilizes treatment practices and participates in research to provide drinking water that “consistently exceeds EPA standards”7. Clean Water Action is a non-governmental organization focusing on clean water advocacy with a commitment to protecting water sources and human health8. They have many locations across the country, including one in Philadelphia. Clean Water Action’s mission statement aligns with ideas of social justice within the greater definition of sustainability. Drink Philly Tap is another nongovernmental organization committed to advocating that Philadelphia residents drink tap water instead of bottled water to reduce plastic waste9. Stakeholders invested in the cleanliness of their water supply extend beyond these organizations, as clean water is a human right that concerns every individual in the Philadelphia region.

Policies & Solutions

The Delaware river used to be one of the United States’ filthiest, polluted with sewage, trash, oil, and toxic industrial waste before the EPA’s Clean Water Act was passed in 19729. Overall, the Clean Water Act has been remarkably successful. Pollution has been kept out of US rivers, and the number of waters that meet clean water goals nationwide has doubled, resulting in direct benefits for drinking water quality, public health, recreation, and wildlife. The Philadelphia Water Department continues to uphold EPA regulations instituted by the Clean Water Act, and organizations such as Clean Water Action continue to advocate its values. However, the Clean Water Act could be improved to widen its focus, since it only focuses on point source pollution. Stormwater, urban runoff from industrial facilities, and pollution from households may not be accounted for in the same way as traceable contaminants due to the fact that non point source pollution is more difficult to regulate from a policy standpoint.

Additionally, some pollutants such as PFAS are incredibly difficult to extract from the water supply, making reparations a costly, convoluted process. The Philadelphia Water Department has been periodically testing for PFAS since 2019. In 2021 and 2022, they monitored PFAS levels at three drinking water treatment plants across the city: Baxter, Queen Lane, and Belmont. Baxter draws water from the Delaware River, and Queen Lane and Belmont draw water from the Schuylkill River10. While monitoring is within the capabilities of the Philadelphia Water Department, PFAS contamination is the result of decades of environmental pollution and is a problem that cannot be solved by water utilities alone. The Philadelphia Water Department stresses that PFAS producers and manufacturers must be held accountable for the control of this pollution at its sources and for its cleanup throughout the region10. There are some existing innovations that assist with PFAS remediation, but they are costly. Technology shown to be effective with PFAS removal and treatment include certain filtration systems, such as reverse osmosis filters, nanofiltration, and high pressure membranes11. Cleanup of PFAS discharging sites is being handled on a national scale through federal funding from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal12, while highly impacted areas continue to test and monitor. This federal policy also aims to provide funding for lead removal from drinking water. President Biden has announced $500 million for Philadelphia water upgrades and lead service removal13.

On a smaller scale, The Philadelphia Water Department focuses on the removal of microplastics from waterways, the management of stormwater runoff, and the recovery of gray water to decrease water waste. One of the most effective ways to reduce microplastics in drinking water is to reduce the amount of macroplastics in waterways. Macroplastics include bottles, bags, tires, and packaging that litter rivers and streams and break down into microplastic particles14. The Philadelphia Water Department operates skimming vessels – boats that “skim” floating litter from the surface of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. On average, each small skimming vessel collects approximately 1.1 tons of plastic per year14. The Philadelphia Water Department also regularly performs maintenance of the city’s sewer system, where microplastics will often enter through stormwater drains. An estimated 1,000 tons of plastics are removed each year through sewer maintenance and other operations14. To tackle sewer management, the Philadelphia Water Department has created a 25 year plan to reduce the volume of stormwater entering combined sewers using green infrastructure, and to expand stormwater treatment capacity through infrastructure improvements6. Through green stormwater infrastructure, stormwater is soaked up by plants and soil. Increasing vegetation within the city’s infrastructure increases the amount of absorbent surfaces present to soak up stormwater runoff, which in turn decreases risks of flooding and makes for cleaner waterways. Through combined policy implementation and infrastructural redesign, strides have been made in the city of Philadelphia to ensure clean waterways and safe sources of drinking water. While contaminants are still present, efforts are being implemented on both a state and federal scale to improve the safety of Philadelphia’s drinking water. The improvements implemented by city departments, non-governmental organizations, and by federal agencies honor the values of sustainability by recognizing clean water as a social justice issue and human right.

Clean Water Assets

– Philadelphia Water Department, 1101 Market St, Philadelphia, PA 19107

– Clean Water Action, 1315 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19107

References

1“About PWD – Philadelphia Water Department.” n.d. Philadelphia Water Department. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://water.phila.gov/about-pwd/.

9“Clean Water Act: 50 Years in Philadelphia – Philadelphia Water Department.” n.d. Philadelphia

Water Department. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://water.phila.gov/drops/cwa50/. 7“Drinking Water Quality – Philadelphia Water Department.” n.d. Philadelphia Water Department. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://water.phila.gov/quality/.

12“FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Nearly $6 Billion for Clean Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure as Part of Investing in America Tour.” 2024. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/02/20/fact-sheet-bid en-harris-administration-announces-nearly-6-billion-for-clean-drinking-water-and-waste water-infrastructure-as-part-of-investing-in-america-tour/.

13“FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces $500 Million for Philadelphia Water Upgrades and Lead Service Removal.” 2023. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/02/02/fact-sheet-pre sident-biden-announces-500-million-for-philadelphia-water-upgrades-and-lead-service-re moval/.

6“Green City Clean Waters – Philadelphia Water Department.” n.d. Philadelphia Water Department. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://water.phila.gov/green-city/.

14“Microplastics – Philadelphia Water Department.” n.d. Philadelphia Water Department. Accessed March 7, 2024.

https://water.phila.gov/sustainability/watershed-protection/microplastics/.

8“Pennsylvania.” n.d. Clean Water Action. Accessed March 6, 2024.

https://cleanwater.org/states/pennsylvania.

10“PFAS Management – Philadelphia Water Department.” n.d. Philadelphia Water Department. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://water.phila.gov/sustainability/watershed-protection/pfas/.

11“PFAS Treatment in Drinking Water and Wastewater – State of the Science | US EPA.” 2023. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/research-states/pfas-treatment-drinking-water-and-wastewater-state-science.

3“Philadelphia region among hotspots for PFAS in tap water, study finds.” 2023. WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/pfas-private-public-drinking-water-us-geological-survey-study-p hiladelphia/.

2“Philadelphia Water Quality | Philadelphia Drinking Water.” n.d. Hydroviv. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://www.hydroviv.com/blogs/water-quality-report/philadelphia.

9“Pledge.” n.d. Drink Philly Tap. Accessed March 6, 2024.

https://drinkphillytap.org/pledge/?tap=.

4“Toxic PFAS found in several Philadelphia rivers and streams.” 2023. WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/pennsylvania-rivers-streams-pfas-found/.

5“WILLOW GROVE NAVAL AIR AND AIR RESERVE STATION | Superfund Site Profile | Superfund Site Information | US EPA.” n.d. gov.epa.cfpub. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.Cleanup&id =0303820#bkground.